From Oscar of Between, Part 26A Excerpt

by

Betsy Warland

The room was once white, was still white enough to converse with daylight. The room’s shape suited Oscar: the walls behind the head of the bed and to the left were right-angled walls; the wall at the foot of the bed started off conventionally enough but after the doorway veered left – ran kitty corner to the middle of the exterior wall – then straightened out to accommodate a pair of rectangular windows whose visage was the exterior terracotta brick wall veined with dormant ivy, the small back porch and accompanying metal spiral staircase, the V of the clothesline strung from the backyard pole to Denis’ porch and his neighbour’s next door, the three-story brick walk-ups with spiral staircases across the back laneway topped with the unambiguous Montreal sky. Oscar relished the luxury of lying in bed looking out the window at the petite narratives that transpired heedlessly there.

The room’s companions are simple:

a small, white set of drawers; a white and black director’s chair; a small closet on the left wall. The floor is the original, varnished pine.

Photo credit: Oscar

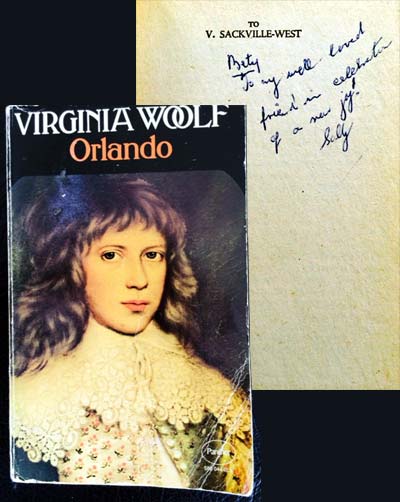

After her initial elation of being back in Montreal, sleep eludes Oscar. At 2 AM she turns on the light; opens Orlando – Biography. It’s been decades since she read it. Only recently did it strike her that Oscar and Orlando may be literary companions. It’s a pocketbook: 1977 Panther Granada edition. The paper is coarse and browned with time. She reads the first page, a Short Biography. The sentence “Recurring bouts of madness plagued both her childhood and married life and in April 1941 Virginia Woolf took her life” startles Oscar with its confident use of the term “madness.” Then Oscar thinks of her visit to Monk’s House last spring — how peaceful it was, how at home she felt.

On the Preface page, Oscar puzzled that Woolf’s extensive acknowledgements don’t mention Vita. She flips to the next page:

To V. Sackville-West.

Immediately below is an inscription in blue ink. Oscar begins to turn the page. Assumes it’s a second-hand book that’s inscribed to a stranger but the handwriting’s jaunty slant upward catches her eye. She looks closer. Reads. Is taken aback. It’s inscribed to her.

Betsy,

To my well-loved friend in celebration

of a new joy!

Sally

Photo credit: Oscar

Oscar rereads the inscription. Sally? Then it sinks in. Toronto. The ’70s. Sally was Oscar’s dear friend who believed in Oscar as a writer, edited some of her early poems. Sally. Three decades older than Oscar, Sally lamented the sheer proliferation of books since the turn of the century that made it no longer possible to read all the classics in one’s lifetime. Oscar’s first book dedicated to Sally. Included a suite of poems about Sally’s death.

Now. In the middle of this sleepless night, Oscar holds this trace of Sally in her hands. A sob gathers inside but cannot find its way out.

Oscar. Too stunned to cry. Stunned by how written words have a life a logic a will of their own, have an eerie sense of their own timing.

What did Sally’s reference to “new joy!” mean? Think context. Then Oscar gets it. It’s a reference to Oscar falling in love with J, Oscar’s first soft-lipped lover.

Earlier that evening, when reading Camouflage (the book accompanying the Imperial War Museum’s exhibit), Oscar notices a connection she hasn’t before:

“… the range of these early guns was not

long enough to enable soldiers to hide and

fire at the same time. This changed with

the invention of the rifle.”

Facing off in close range, side-by-side in opposing lines of bright-coloured uniforms, firing volley after volley until “one side decided it had had enough and ran” morphed into unpredictable proximities, stealth, stalking, surprise attacks.

The rifle = distance = camouflage = disassociation.

Photo credit: Cathleen With

Guest Writer:

Cathleen With

Vancouver, BC

Cathleen With online

When I wake up there’s been another earthquake.

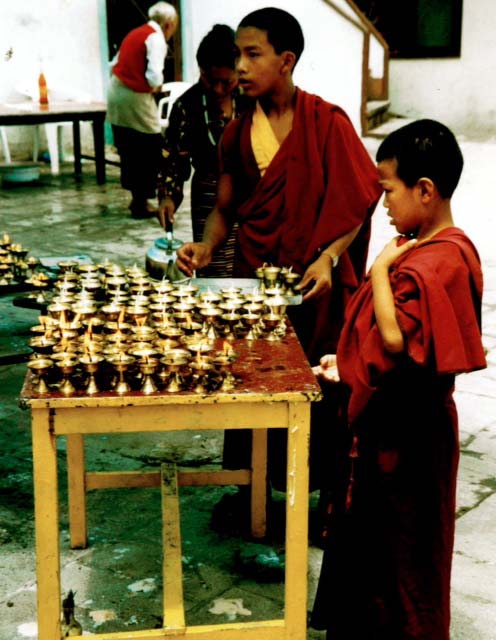

When I go to sleep, three days later they’re still pulling people out of the rubble, out from under little shops that sold tea and loose pants in a myriad of colours, out of the store where Champan served me tea with honey, the bangles and necklaces and silver earrings imprinted with Buddha and yin and yang signs. The eyes of the temple, Swayambhu, following me.

When I think of Kathmandu I remember, 20 years to the month, searching shops for the best hiking boots. Boots that will break in easily for Annapurna Sanctuary. I browse flyers for trekking partners, I look for lone women in their 20s because Janey was supposed to be here with me but she got a primo job in Victoria and I can’t blame her. I compose letters to her in my head to send from the GPO, and I pick up beautifully written missives from her at Poste Restante, no internet, expensive phones. I call my mother once a week, and sometimes go for weeks without speaking much English. And my mind is soothed by this break, I am at home with my thoughts and books that I read and reread: Beloved, Woman on the Edge of Time, Housekeeping. Housekeeping is my favourite. I sing myself to sleep with: “Good night, Irene” and imagine that Sylvie and Ruth are here in Kathmandu with me, waiting to trek, waiting to push ourselves around the eighth highest mountain in the world.

The trekking partners I meet are two fun Brits, sisters from Cheshire. Which is weird because this is where Janey is originally from and they even look like her. How Bob, a man with Down’s Syndrome at our group home job, calls her: Janey Janey with the yellow yellow hair. I feel at home walking with them and it’s not long before we are singing whole soundtracks to The Sound of Music, A Chorus Line, South Pacific. It feels odd to feel at home in this Nepalese country, the children smiling hellos to us as we pass, the kids in their traditional clothes waving, entreating us to take pictures of them. We have brought US dollars for this purpose; the green holds more cachet than the Nepalese rupee. Their parents make us noodles and chicken wings at their lodges, perfectly spaced for around eight hours a day of hiking. We eat, exhausted, crawl into warm sleeping bags and sleep together like we’re coffined.

And today they pull out a little boy who was doing his two years schooling at a monk’s residence. His face ashen and his hands moving over the prayer beads around his neck. He is blank-faced and whispering, staring down the camera, lips chapped, face sunken. It is Day 5 and people bless him as he passes in his ambulance cot, his family buried.

The boys would light the candles every night, Champan told me every light is a soul they pray for.

We’d watch them, wonder about all those souls, the sun going down behind the eyes of Swayambhu.

I think about Kathmandu now, pray for the light. Pray for the souls.

Photo credit: Cathleen With

Photo credit: DJ Blades

Featured Reader:

Barbara Kuhne

Vancouver, BC

I read Oscar’s Salon because

I read Oscar’s Salon because it surprises and challenges concepts/precepts/preconceptions. I read it for the disparate voices, the juxtapositions, the call and response. I read Oscar’s Salon because it is a testament to truth-telling.

Profile

Barbara Kuhne is a former feminist press publisher, an avid reader, and a book editor.

This month, I feel as though I am brought in close for the intimate details of life, like someone’s inscription in a book, their handwriting, a memory of a kiss, the sob of grief, the smiling faces of children, a meal of noodles and chicken wings, that feeling right before sleep when all the body’s muscles have worked. I am also pulled in close by the details of how near a gun needed to be to its target, an intimation of contact, connection, the imagined dotted lines between two human beings before the trigger is pulled. And also the souls, sparkling like candle lights, as each one is blown out in one swift move of the earth.

Oscar is gorgeous. I started crying for Oscar, me, and all those lovely people in Kathmandu who didn’t make it. Little kid monks included. Life is an inscription: a fleeting, warm quickening. Thank you for asking me to be a part of this.

Every month, Oscar pulls me in. Oscar’s experiences are so particular and so very different from my life, yet somehow I always feel like Oscar is about me. Betsy, your voice is so intimately private, yet you make me feel I belong here, inside your story. Each excerpt moves me in its own way. With this one, it’s that poignant turning, where Oscar realizes the book is inscribed not to a previous owner, but to Betsy. Oh, that line, “A sob gathers inside but cannot find its way out.” So beautiful!

Things surviving, coming to the surface, out of hiding, unburied, still existing, so much lost. “Stunned by how written words have a life a logic a will of their own, have an eerie sense of their own timing.” Stunned by how the narratives here are a parallax, the reader and the reading coming together over distance, closing in as the narratives collide through proximity, frisson. This project is so innovative, so direct, so unadorned. I love it.

Is memory a form of emotion? Or, are memory and emotion sides of the same coin? When the penny drops. Memory and emotion are spatially shaped, stored, released. Both Cathleen and Oscar’s pieces evidence this. The unpredictability of this! Hawking’s radical retraction of Black Hole Theory upon realizing matter changes but cannot be trapped or disappear. Is shredded but not destroyed. Claudia struck by how these two narratives are a parallax within themselves and in adjacency. The unpredictability of all of this! Unforeseen alignments that re-boot story shreds. Make them new. Make us write. Make us read.