Excerpt from Oscar of Between, Part 13

by

Betsy Warland

March 2009. Sunlight on sheet of writing paper reminiscent of Montreal but different. Here – being Vancouver – it being morning sun. There it was afternoon through window overlooking rue Boyer. Here, this light warm, diffuse. There, it was focused, almost blaring through glass. Oscar thinking on memory and membership. Recalling Simon McBurney startling audience at a Jewish Book Fair panel a year ago when asked how it felt to be back in London again (having just arrived from the airport). Assumption: UK his home. Simon replying that he actually felt more at home in Japan where he’s indisputably an outsider. In London he’s an outsider where he’s supposed to belong.

This said. Simply. As fact.

At the source.

First assessment in Montreal not gender but cultural. Francophone? Or, Anglophone? Who is speaking to whom? This, determining what is said. What is not. And, the how and why of what is meant.

In a foreign country, to be free of this with all its sharp edges; current along in the evident present like a child who leaves navigation of social rules and backstories to the adults.

Oscar in Denis’ apartment.

He in hers.

Not having met but sharing mutual friend.

On the phone they had spoken of their art, books, and music, had been drawn to each other’s voices. When Oscar unlocks Denis’ door and walks in, their apartments initially appear to be quite disparate but soon they discover delightful correspondences: stones nestled throughout, Chinese tea cups, same rectangular woven-grass baskets, bull clips on opened bags of food, and images here & there of spiritual figures – Christian for Denis; Buddhist for Oscar.

Oscar. Finds. It oddly comforting. To submerge. Into Denis’ memory-infused belongings that emit tenderness yet remain untranslatable.

For the next few days, Oscar is relearning Montreal. Erratically stumbling upon memories of visits there with Daphne. Then, later, other memories of being there with Susan. Les Entretiens, Place des Arts, the rental on Sainte Famille, luminous azure fall night sky, Lise’s apartment, that particular pathway on Mont Royal.

Sharing of memories

– the loss of –

quietly

devastating.

Oscar in her sixty-second year. The list of deaths, divorces, dissociations, driftings away lengthening. The dialogical nature of memory steadily eroding: companioned recollection becoming solitary recollection. Insistent accretion of this particular sorrow. This. Perhaps, the greatest grief.

This. Perhaps.

What is the image for this? The metaphor for memory isolation? Where are the symbols in public representation? The statues? Memorials? Plaques? A face surfaces in Oscar’s mind.

Face in a film.

Haunting close-up in Werner Herzog’s Where the Green Ants Dream. Still gaze of elderly aboriginal man in the Outback. Gaze utterly void of anticipating reciprocity yet open. This man, we learn, is the sole speaker of his tribe’s language.

Only one still alive.Two decades later. His face.

Incised in Oscar’s mind.

“Language is an argument against loss.”

Anne Michaels.

“In Conversation with Hall Wake.” Last night at St. Andrew’s-Wesley United Church. Burrard Street. Downtown Vancouver (sensation of entering the grey stone, vault-like building). Discussing her new novel The Winter Vault Michaels affirms, yes, there is “no unneeded word” in her writing. This alertness evident in Michaels’ response to every question. Oscar struck by her moral and artistic integrity. And, her grief.

Acceleration of loss. Michaels’ noting that language is increasingly all we have left, that fewer and fewer of us are buried where we grew up, that so much left behind, taken from us, discarded, destroyed.

Oscar thinking language can also promote loss. Instill forgetting. Highjack veracity.

Michaels’ unease with the rampant production of replicas as a kind of erasure.

Shared memories. Loss of. Oscar puzzling: why does she mourn it so?

It’s something about memory being a profound form of intimacy itself. That remains loyal. Regardless. Even when we seem, or seek, to forget.

How it’s unbound by time in our recollecting mind. Not confined by its historical moment. Is imperious to our life changes.

Then Oscar wondering. Perhaps memory is not so much ours as we are its. We being merely a vehicle for it.

Its worker bees.

Oscar and a writing friend in the Vancouver Art Gallery café, talking writing and telling stories about their unfolding lives over lattes. Rainy Sunday afternoon. The city emptied out — calm — on Easter weekend, they talk about family memories and her friend’s urgency to bring them into her manuscript (both parents having died recently). So many stories in need of rescue.

They speak in almost hushed tones.

Then image of Joan Didion’s reaction to one of the interviewer’s questions in a documentary she saw in Montreal flashes in Oscar’s mind.

“It must have been very difficult for you to write this book. What prompted you to write The Year of Magical Thinking?”

– high-beams of Didion’s eyes –

“No one had ever prepared me for what grief is.”

Large shopping bag chock-a-block with produce slung over Oscar’s shoulder, Oscar weaving through aisles at Granville Island Market heading for Italian pasta shop for last item on list when in crush-of-bodies Oscar’s hand brushes against astonishing soft-warmth. Shock.

“What was that?”

Then, she recognizes it: hand of a small child. At two o’clock in a back carrier.

Her son.

At that age.

Inside, Oscar crumples on the floor.

Outside, Oscar takes a few more brisk steps.

Arrives at the shelves and shelves of olive oil.

Guest Writer:

Shaena Lambert

Vancouver, BC

shaenalambert.com

Excerpt from “The War between the Men and the Women,” from Oh, My Darling, a collection of stories published Fall, 2013, HarperCollins.

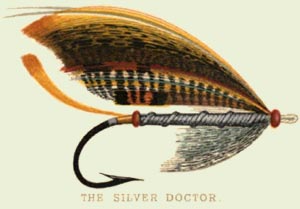

When Jane cries out from the bed, her mother Gretchen is there, blocking the hall light, lying down beside her. To distract Jane, Gretchen sings songs, or recites the fishing flies she knows how to tie — tricks her father taught her growing up on a remote lake in the Shuswaps,

Photo credit: Wikimedia

in the interior of the province, during the war. Silhouetted damsels. Deer-haired nymphs. Goldenheads. Silver Doctors. These names cause a ruckus and shine in Jane’s head. She pictures that remote fishing lodge with its cook house, and eight wooden cabins with green shutters that can be raised and lowered on hinges. Wood stoves for heat. Four outhouses.

It is her mother’s loneliness that Jane feels, each time she hears the stories. Jane closes her eyes, and she can see her as a little girl running after her father through the long grass, and this image radiates a great throb of loneliness from its center.

She sees her grandfather Hans pulling on his work boots, and then walking past the cabins to stand on the dock. Gretchen slips without a word into the bow of the rowboat. She feels the thunk of the oar blade against the dock as they push away, shooting across the reeds toward the dark side of the lake. Hans casts and trout come to his hook, but Gretchen, aged five, doesn’t care about the fish anymore.

“How many days?”

First it is one hundred sixteen. Then eighty-three. Then – miraculously – sixteen. Sixteen days until the end of banishment. Sixteen days until the first day of school.

Gretchen sees her father looking toward the end of the lake where the outlier cabin sits in its private cove. One of its shutters is off kilter. He rows into the bay, ties up to a sapling, and they walk up the trail investigate. Hans yanks open the door and mattress ticking floats everywhere. The bed has been knifed open, canisters overturned, bacon grease and cornmeal spread on the floor to form a messy swastika. And the worst part – someone has taken a shit on an enamel plate and left it on the card table.

As for the first day of school at Sicamous Elementary – it was inevitable – how could it not be? This little girl from the woods was bound for sorrow, just like a character in one of the folk songs Gretchen sang. No friends were going to gather around her in pastel dresses, bows in their hair: not likely. She was an enemy alien with scabbed knees and a German name, whose jacket smelled of wood smoke, whose parents couldn’t afford saddle shoes. What happened next was as inevitable as coughing, as lying down, as dying – and Jane wishes, whenever she hears the story, that she could go back in time, step from behind a corner of the school house, walk past the tittering girls and take her mother’s hand. I’ll play with you, is what she would say, if she had that kind of power.

Eagle Valley School Photo credit: Sicamous and District Museum and Historical Society

Shaena made me cry. I had an easy school life. Kept home until almost 9yrs old and able to read, write, etc. upon entry. Still this was my first learning of loss and grief: the erosion of innocence and wonder through enforcement of models from which to view my world. Betsy made me gasp: even outside the school framework, losing tenderness of skin(body) and spirit(will to be) is a process of immersion and loss. The dipping in and then dripping off of world and being that kills the firm knowledge of where I came from and destroys awareness that I am perfect. At 66 a carelessness for memory (brought on by super successful grievings in the past) leaves me between my life and the end of it. I live within the vacuum of present. A vacuum that builds and collapses with the touch of a child and child talk that triggers memory which cannot be articulated. It vibrates a solitary note that resonates. As a Hospice Nurse I met people who had worked through their grief too early and were left with loved ones who were still alive. Perhaps the post grievers felt this dichotomy of joy and indifference.

“:I’ll play with you is what she would say if she had that kind of power.”

I’ll pick it up there, though my urge is to leave the computer and weep.As I wept after seeing The Book Thief that left me shattered. In the film, one small boy does just that. He plays with the outsider and becomes her friend.And having even one friend is a thread of hope in a world where life, for some, is unbearably, unimaginably dreadful.

But why must we keep creating outsiders? What is this inborn tribalism that trumps caring and curiosity alike? That labels “other”in negative terms? That scoops up the turds of hatefulness and fashions them into idols akin to Marilyn’s models from which to view the world?

Can a vacuum be conceptualized without a defining exterior? Do we not all live in bubbles of our own creation, bubbles that we know will collapse, but hopefully, not yet?

Inside, Oscar crumples on the floor. Outside, Oscar takes a few more steps.

Betsy:

Oscar. Finds. It oddly comforting. To submerge. Into Denis’ memory-infused belongings that emit tenderness yet remain untranslatable.

Shaena:

Silhouetted damsels. Deer-haired nymphs. Goldenheads. Silver Doctors. These names cause a ruckus and shine in Jane’s head. She pictures that remote fishing lodge with its cook house, and eight wooden cabins with green shutters that can be raised and lowered on hinges. Wood stoves for heat. Four outhouses.

Betsy:

The dialogical nature of memory steadily eroding: companioned recollection becoming solitary recollection. Insistent accretion of this particular sorrow. This. Perhaps, the greatest grief.

Shaena:

It is her mother’s loneliness that Jane feels, each time she hears the stories. Jane closes her eyes, and she can see her as a little girl running after her father through the long grass, and this image radiates a great throb of loneliness from its center.

These excerpts are so well synced. Compare and contrast. I appreciate Marilyn`s comments: `Shaena made me cry… Betsy made me gasp.` I had a similar response.

In these excerpts, I feel like one writer allows head to lead heart, and one writer is allows heart to lead head. Both to stunning effect. As an emerging writer, it`s easy to forget that there are many ways to get an idea across. There`s not only one correct way to communicate. Do you feel trapped by your notions of `correctness` when is comes to communication? Storytelling?

have come back to these 2 excerpts after reading them over 2 weeks ago. as writer & facilitator for other writers—question pulsing inside: how does feeling translate through words on page or screen? and isn’t it here in intimacy (in-to-me-see as my friend sarah k speaks it) between reader & companion voice in head as we read/write, the ‘other’ the ‘outsider’ is brought inside.

I return to the Oscar project each time with renewed awe and reverence for its peregrinations, its careful re-routing of thought, memory and loss, its brilliant form. Love, in particular, how the project materializes aging and the archive of vision it offers. The project’s trenchant love and critique of language: “Oscar thinking language can also promote loss. Instill forgetting. Highjack veracity.”

and this: “Then Oscar wondering. Perhaps memory is not so much ours as we are its. We being merely a vehicle for it. / Its worker bees.”

Besty- I want to read this as a book! Something to return to, over and over again. To start again, each time.

Shaena’s fragment clutches and releases, moving fast through so many different pitches and registers- beauty, violence and the impossible distance of the past, ” What happened next was as inevitable as coughing, as lying down, as dying.”

oops! I meant Betsy…not Besty 🙂

appreciate your comment najwa about the way oscar tracks language and time—relationship. yes a book indeed!

Thank you Marilyn, Helen, Carleigh, Ingrid, and Najwa for articulating your eye-to-eye, nose-to-nose encounters with Oscar’s and Shaena’s excerpts. I find myself rolling around in each of your thought-provoking comments like my dog used to do when he found a particularly intoxicating scent in the grass! This “Part 14, Excerpt A” had me dangling at the end of the limb. The vulnerabilities the subject called up made me afraid of sounding pathetic. It reminded me of how quickly we can corrupt language; violate its integrity; forcefully bend narrative to manipulate how it enters others minds. Fortunately, there is a particular elation when I entrust myself to the narrative that compasses me (V. Woolf “when the pen gets on the scent”). Lately, I’ve found myself saying that publishing Oscar’s Salon is my most satisfying experience to date, as is the level of engagement and immediacy of the Salon’s readers. I hope you can sense that you, dear commenters, are no small part of this.